|

|

||||

Microbes, including eubacteria, archaea, and single celled eukaryotes, are the dominant forms of life on earth. They dominate "large" organisms like us in absolute numbers, biomass, habitat dominance, and phylogenetic diversity. During more than half of the Earth's history, only microbes existed. It has been known for over thirty years that, in the human body there are ten times more microbial cells than human cells. Microbial genes outnumber human genes in each of us by at least two orders of magnitude. Microbial physiology is a dominant factor in carbon cycling, greenhouse gas emission and oxygen production. Microbes live deep in the earth's crust, in the deep ocean, in frozen and boiling waters, and in both highly acidic and highly basic environments. However, over 97% of all microbes cannot be cultivated, which has significantly biased existing model systems and microbial genome sequencing projects. Consequently, we have until recently it has been difficult to appreciate the complexity and function of some of the most important ecological players on earth.

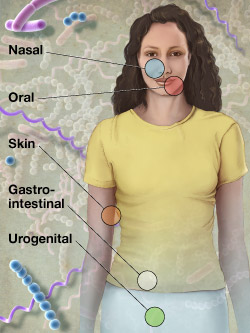

Fortunately, new sequencing and bioinformatics technologies such as tagged barcoding, community genomics, pyrosequencing and metagenomics, large scale genotyping, and large scale genome sequencing have made it possible to study the structure, function and dynamics of microbial communities in natural microbiomes. Surveys of the human microbiome are emerging, including the microbiomes of the gastrointestinal tract, skin, reproductive tracts, and oral cavities, along with their affects on obesity, women's health, peradontal disease, and other human health concerns. Ecological surveys of soil, air, and water are emerging in order to understand the consequences of climate change, pollution, deforrestation, and agricultural practices. Studies of microbial consortia in extreme environments are shedding light on the origins of life, and on possible mechanisms for bioremediation of severely poluted sites. At the same time, new bioinformatics tools and community resources for storing and analyzing community genomic data are coming online.

Nonetheless, microbiome studies are scarcely in their infancy. Most natural ecosystems remain uncharacterized. Many human microbiome sites have not been studied at all, and even fewer comparative studies of microbiomes in healthy versus diseased patients exist. Mechanisms for microbial adaption and ecological engineering are far from systematic. And the computational tools to enable us to meet these needs are in their infancy, at best.

|

James A. Foster, Ph.D. University of Idaho foster _AT uidaho _DOT edu |

Jason Moore, Ph.D. Dartmouth Medical School Jason.H.Moore _AT Dartmouth _DOT edu |

Submitted papers are limited to twelve (12) pages in our publication format. Please format your paper according to instructions found at http://psb.stanford.edu/psb-online/psb-submit/. If figures cannot be easily resized and placed precisely in the text, then it should be clear that with appropriate modifications, the total manuscript length would be within the page limit.

Please note that, unlike many biology conferences, the PSB proceedings is an archival, peer-reviewed publication. PSB publications are indexed in Medline, and should be thought of as short journal articles. Submissions which do not reach this level of publication quality can be disseminated at the meeting through a separate booklet of unrefereed abstracts, and/or by poster presentations.

Contact Russ Altman at psb.hawaii at gmail.com for additional information about paper submission requirements.